Nazi Germany’s Persecution of Jewish Artists and Art

The Nazis specifically targeted and “singled out” Jewish artists and their work as part of their broader campaign against “degenerate art,” which they viewed as corrupting German culture [1-7]. While only six of the 112 artists included in the main 1937 Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition were, in fact, Jewish, the Nazis frequently identified modernism as “Jewish-Bolshevist” and used anti-Semitic rhetoric to condemn it [6, 8-11].

Here are some of the Jewish artists who were singled out by the Nazis:

Jankel Adler,

Marc Chagall,

Hans Feibusch,

Otto Freundlich,

Hanns Katz,

Max Liebermann,

Ludwig Meidner,

Lasar Segall,

Georg Wollheim

•

Broncia Koller-Pinell (1863-1934): Born in what is now Poland and raised in Austria, Koller-Pinell was a modernist painter whose popularity extended to Germany [12]. With the rise of Nazism, her art and Jewish origins made her persona non grata, leading to her being banned, neglected, and largely forgotten in mainstream art history after her death in 1934 [12]. She was among the talented women artists banned or imprisoned and forgotten [1].

•

Ilse Twardowski-Conrat (1880-1942): Born into a Jewish family in Vienna, Twardowski-Conrat was a talented sculptor who gained recognition and commissions, including from Empress Elisabeth of Austria [13]. By the 1930s, after moving to Munich, Nazi art policies forbade her from practicing her work [13]. She was stripped of her rights, forced to move into a Jewish community without her possessions in 1942, and chose to take her own life rather than submit further to the Nazis [13].

•

Friedl Dicker-Brandeis (1898-1944): Also born in Vienna, Dicker-Brandeis was a versatile artist proficient in painting, textile design, and printmaking, who devoted her life to studying and teaching art [14]. She was deemed “degenerate” by the Nazi party and was vocal against their policies through her work [14]. She was interrogated by the SS, sent to the Theresienstadt concentration camp where she taught art to Jewish children, and was later murdered in Auschwitz in 1944 [14].

•

Marc Chagall (1887-1985): Born in Russia, Chagall’s life and paintings were deeply rooted in Jewish tradition and religion, using “crayon colors and joyous renderings” [15]. His work was ridiculed in the Entartete Kunst exhibition [15]. The Nazis specifically feared his imagination and hated anything Jewish or Eastern European in his art [16]. Three of his early paintings, “Dorfszene” (Village scene), “Die Prise” (Rabbi), and “Winter,” were hung in the “Jewish” gallery (Room 2) of the exhibition [17-19]. His “Die Prise” (Rabbi) was even featured in a window display with the sign, “Taxpayer, you should know how your money was spent,” to incite public outrage [20, 21]. Chagall was one of the artists whose works were seized from German museums [4, 22]. Fortunately, he was among the prominent artists rescued from German-controlled Europe by Varian Fry and the Emergency Rescue Committee (now the International Rescue Committee), emigrating to America shortly before the Nazis occupied France [17, 23].

•

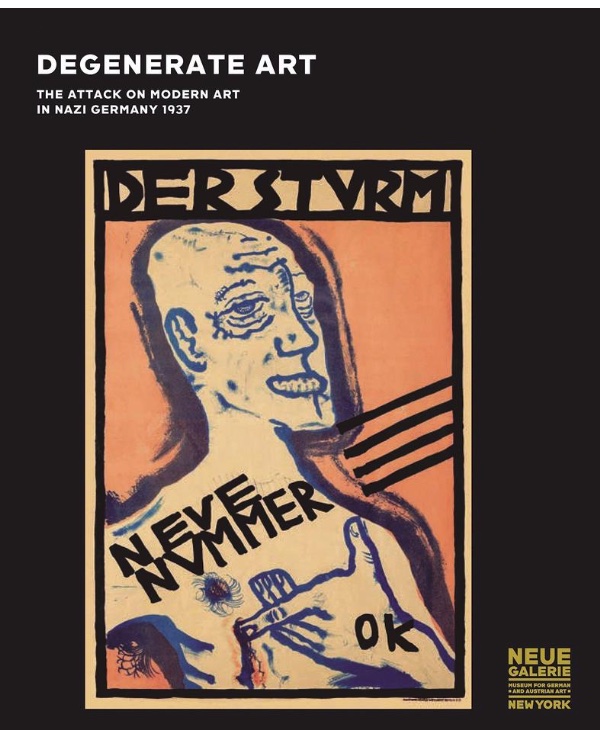

Otto Freundlich (1878-1943): Freundlich, identified as a “Jew, communist, and modern artist,” was considered a “perfect enemy of the Nazis” [24]. Fourteen of his works were confiscated, including his 1.40-meter high monumental sculpture “Big Head” (also titled “The New Man”), which was prominently featured on the front of the Entartete Kunst exhibition’s accompanying booklet [24-27]. The sculpture was later destroyed, and a clumsy replica may have been made to appear more “African” to align with racist Nazi ideas [24]. His work was also grouped in the exhibition under the title, “Three specimens of Jewish sculpture and painting” [28, 29].

•

Hanns Ludwig Katz (1892–1940): A German painter and graphic artist, Katz was one of the few Jewish artists whose work was included in the 1937 Entartete Kunst exhibition [30, 31]. After the Nazi takeover in 1933, he actively participated in the Frankfurt section of the Juedischer Kulturbund [32]. He immigrated to South Africa in 1936, thus escaping before one of his expressionist portraits was publicly denounced in Degenerate Art in 1938 [32]. His work, along with that of Jankel Adler and Ludwig Meidner, was invalidated by being grouped under the slogan, “Revelation of the Jewish racial soul” [33].

•

Ludwig Meidner (1884-1966): Born into a Jewish family, Meidner’s self-portrait from 1912 was featured in the Entartete Kunst exhibition as one of “Three specimens of Jewish sculpture and painting” [28, 29, 34]. His work was displayed in the “Jewish” gallery (Room 2) under the heading, “Revelation of the Jewish racial soul,” with the comment “Jewish, all too Jewish” [28, 29, 35, 36]. Eighty-four of his “degenerate” works were seized from public institutions [28, 29]. He was also known for creating graphic works on Jewish themes published by the Verlag für Jüdische Kunst und Kultur [37, 38]. The Kristallnacht pogrom in 1938 prompted him and his family to flee to England with the help of Augustus John [39, 40].

•

Max Liebermann (1847-1935): Although he died before the main 1937 exhibition, Liebermann, a prominent Impressionist painter, was Jewish and became a target of anti-Semitic criticism throughout his career [6, 10, 41-44]. The Nazis considered him Jewish, and despite his contributions to German modernism, he was among the artists persecuted [6, 10, 44]. He was expelled from the Prussian Academy in Berlin [10, 45]. His realism was often linked to his Jewishness by critics, both anti-Semitic and some Zionists [46, 47]. After his death, in 1941 or 1942, a painting and drawings by Liebermann were instructed to be sold through Hildebrand Gurlitt, with the reasoning that the client was likely a Jewish émigré who could take the “painted piece of cardboard” out of the country [48, 49].

The Nazis often distorted or misinterpreted artists’ manifestos, mocked their creations with graffiti and derogatory labels, and greatly exaggerated the prices museums paid for the art to further incite public revulsion [2, 8, 50-55]. They also established segregated cultural organizations, like the Jüdischer Kulturbund, for Jewish artists and audiences, ironically reflecting traditional views of their own art as classical or folkloristic [56]. The broader Nazi cultural policy demanded “racial purity among the artists and their compliance with the Nazi Party,” deeming any modern art as “pornographic, insulting, pathologically sick,” and backed by Communists and Zionists [3, 57, 58].

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.